The ways that consumers engage with flexibility is evolving. In my last blog, I explained how consumers currently experience grid flexibility and what they need to consider when actively participating. Now, let’s delve into the interplay of time-of-use tariffs and markets, and how this impacts both the system and consumers.

The system impact of time-of-use tariffs

Today, there is no explicit link between energy price-based incentives and those originating from the needs of running the electricity system.

Time-of-use tariffs (ToU tariffs) operate independently of the grid; neither retailers nor consumers take the grid infrastructure into account when making their decisions. This leads to certain consequences, that markets can help resolve.

Consumer herding?

When electric vehicle users all try to charge at the same time to take advantage of low prices, it can create spikes in demand that strain the grid.

This type of herding behaviour is a major challenge for distribution grids. The problem only gets worse as more EVs hit the road.

There is still debate as to whether consumer herding will fully materialise. Some argue that the random nature of end-user behaviour is unlikely to cause significant issues on a hyper-local level.

What the data shows: The impact of ToU tariffs

However, there are datasets that start to show the impact of ToU tariffs on the use of power.

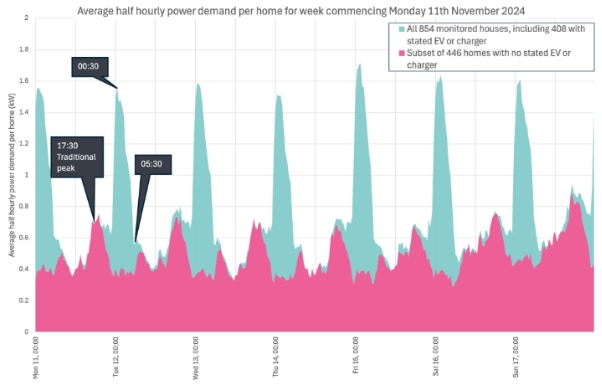

For example, the Energy Systems Catapult’s “Living Lab” provides data that shows the electricity usage patterns for a cohort of households on a time-of-use tariff over a week.

In pink, we see the usage pattern of homes without an EV. In teal, those with an EV. We can clearly see the consumer herding behaviour, where ToU tariffs drive smart charging which results in high demand overnight. The conclusion here is that we will see a shift from cheaper rates overnight, possibly into the middle of the day.

What we see in the above is very localised increases in demand at specific times. This immediately raises the question: what happens to the distribution system at these times and locations?

There is no reason to believe that the patterns we see in Figure 1 will not increase in both occurrence, as more households move to time-of-use tariffs, and magnitude, as more and more electrification occurs.

Constructive and destructive interference

The next thing to do is pull the data on DSO flexibility dispatches from the various open data portals and compare these to the day-ahead wholesale price.

This will let us see the operational decisions DSOs make, and how they align, or otherwise, with the wholesale price which underlays ToU tariffs.

Example one: Demand turn down

Demand turn down is probably what most people think about when it comes to engaging domestic end consumers in flexibility. It incentivises consumers to use less electricity at certain times as per the NESO’s Demand Flexibility Service.

Rather than focussing on the system as a whole – which is what DFS does – let’s take a closer look at the distribution system and at demand turn down dispatches made by the DSO.

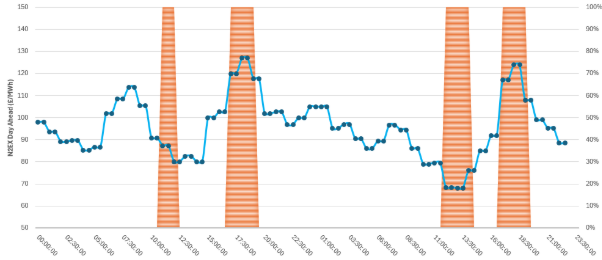

The below dispatch events are for domestic flexibility accessed via suppliers and aggregators. Figure 2 shows two days in March this year. The graph plots the N2EX day-ahead wholesale, as well as turn-down dispatches made by a DSO for domestic flex in orange.

This snapshot of data shows that there are periods where those instructions line up with periods of higher electricity price. In those cases, the energy price and DSO actions are working together to supress demand.

But as suspected, there are times where the DSO is requesting demand turn down, and the energy price is low. This is because there is no direct link between the price of electricity and conditions on the local distribution network.

At a general level, higher prices correspond to times of higher demand. You would assume, therefore, times of higher grid stress results in DSO dispatches – but this is not always the case.

The former thought can be paraphrased as “let the market sort it out”. However, the physical grid often has other ideas.

A free market cannot capture all physical considerations, such as thermal limits, line load factor, available headroom per substation transformer at particular time, etc.

An easy assumption to make is that the DSO needs to take demand turn down actions during times of lower energy prices because of consumer herding, just like we see in Figure 1.

Example two: Demand turn up

We should also look at demand turn up. This provides free or half price energy to domestic end consumers – an enticing offer – and talks to the aim that the energy transition should be of net benefit to the population.

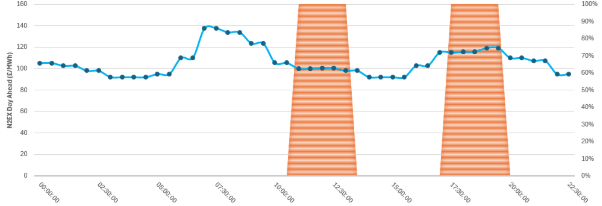

Figure 3 shows the N2EX Day Ahead wholesale price for a day in March versus DSO dispatches for domestic demand turn-up.

Again, we see a similar situation, where the demand turn up is instructed during times of higher energy price. In this example the electricity price is relatively high all day, end consumers are being rewarded to increase their demand, but does this offset the increased exposure to higher prices for those on time-of-use tariffs?

The impact on the end consumer

We can see that there are times when both time-of-use and system flex events align. This means the end consumer can layer on the rewards for being flexible.

But there are also times when the two signals are at odds. The way that the two are presented to the end consumer is dependent on the approach of the supplier, and/or whether there is an independent aggregator at play.

Getting this right is increasingly important and should be one of the major considerations for the next step in consumer-led flex.

Multiple challenges exist:

- From the logistical – for example, not allowing the same MPAN twice in a System Flex event (a conflict where both a supplier and an aggregator want to leverage the same customers flexibility);

- To the economics of the situation: does the level of reward for turning up at a time of high time-of-use prices actually cover the increase in cost?

We are already seeing anecdotal occurrences of issues arising with smart EV charging where cars cannot charge sufficiently during off-peak times because of demand turn down instructions from system flex events.

Ultimately, the cost of system operator flex dispatches is fed back to the end consumer through their bills as network costs. Accessing cheaper power via time-of-use therefore does have knock-on increases in cost, if the result is more grid congestion.

What’s next for consumer-led flexibility?

All too often the narrative around domestic flexibility focusses on supplier time-of-use and type-of-use tariffs. However, it is increasingly important to realise that these alone will not get us to Clean Power 2030 or Net Zero 2050.

The distribution system is key to the energy transition, as this is where most electrification will happen, so we must consider system needs at the local level.

New, dynamic tariffs and the questions left to answer

Optimal presentation of these different needs for flexibility to domestic end users will be key to securing the engagement needed to get to the levels of flexibility required. We need to put effort into getting this right as part of the next step in consumer led flexibility.

There is ongoing interest in so-called “Dynamic Grid Tariffs” that reflect the load on the distribution network as well as the energy price. These have the potential to bridge the gap between energy price and network conditions.

For example, Swiss utility Groupe E, offer a tariff to users with a load lower than 100 MWh/yr the Vario tariff. This reflects the load on the distribution system in the rate. The effectiveness of such tariffs in allowing customers to benefit from cheap energy and avoid overloading the local grid needs to be assessed.

As part of the next step for consumer-led flex, we need to address questions such as:

- How are aggregator and supplier propositions presented to the domestic end consumer in a coherent and understandable manner?

- How do we avoid conflict between time-of-use tariffs and system needs? How do we avoid extra costs to end consumers related to flexibility dispatches that result from time-of-use tariffs?

- How do we engage domestic end consumers without the need to educate them in the details of the power system?

As grid flexibility gains momentum in nations around the globe, these questions will need to be answered, and fast.

A note on zonal electricity prices

It is not possible to talk about this subject without some mention of zonal electricity prices. These are on the table as part of the UK’s reform of electricity market arrangements (REMA). If this is implemented, it will add an additional layer of complexity to this discussion.

While locational electricity prices bring another element of the “system need” to the table, the locational aspect still does not consider the physical infrastructure of the grid or power flows at hyper-local scales.

Zonal pricing could reduce the impact of electrification on networks if it incentivizes locational changes in demand, and/or relocation of generation and demand (somewhat unlikely in the near term). However, it still does not address the needs of the distribution system which are within the broad zones proposed.

Want to learn how Electron’s market platform can help your business? Book a demo.